Confirmation holism

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Confirmation holism, also called epistemological holism is the claim that a scientific theory cannot be tested in isolation; a test of one theory always depends on other theories and hypotheses.

For example, in the first half of the 19th century, astronomers were observing the path of the planet Uranus to see if it conformed to the path predicted by Newton's law of gravitation. It didn't. There were an indeterminate number of possible explanations, such as that the telescopic observations were wrong because of some unknown factor; or that Newton's laws were in error, or that god was causing the perturbation in order to show the hubris of modern science. However, it was eventually accepted that an unknown planet was affecting the path of Uranus, and that the hypothesis that there are seven planets in our solar system was false. Le Verrier calculated the approximate position of the interfering planet and its existence was confirmed in 1846. We now call the planet Neptune.

There are two aspects of confirmation holism. The first is that observations are dependent on theory (sometimes called theory-laden). Before accepting the telescopic observations one must look into the optics of the telescope, the way the mount is constructed in order to ensure that the telescope is pointing in the right direction. The second is that evidence alone is insufficient to determine which theory is correct. Each of the alternatives above might have been correct, but only one was in the end accepted.

That theories can only be tested as they relate to other theories implies that one can always claim that test results that seem to refute a favoured scientific theory have not refuted that theory at all. Rather, one can claim that the test results conflict with predictions because some other theory is false or unrecognised. Maybe the test equipment was out of alignment because the cleaning lady bumped into it the previous night. Or, maybe, there is dark matter in the universe that accounts for the strange motions of some galaxies.

That one cannot unambiguously determine which theory is refuted by unexpected data means that scientists must use judgments about which theories to accept and which to reject. Logic alone does not guide such decisions.

Contents |

The theory-dependence of observations

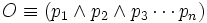

Suppose some theory T' implies an observation O:

The required observation, however, is not made, therefore

So by Modus Tollens,

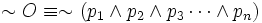

All observations make use of prior assumptions, which can be symbolised as:

and therefore

which is by De Morgan's law equivalent to

.

.

In words, the failure to make some observation only implies the failure of at least one of the prior assumptions that went into making the observation. It is always possible to reject an apparently falsifying observation by claiming that only one of its underlying assumptions is false; since there are an indeterminate number of such assumptions, any observation can potentially be made compatible with any theory. So it is quite valid to use a theory to reject an observation.

The indeterminacy of a theory by evidence

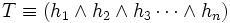

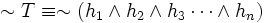

Similarly, a theory consists of some indeterminate conjunction of hypotheses,

and so

which implies that

In words, the failure of some theory implies the failure of at least one of its underlying hypotheses. It is always possible to resurrect a falsified theory by claiming that only one of its underlying hypotheses is false; again, since there are an indeterminate number of such hypotheses, any theory can potentially be made compatible with any particular observation. Therefore it is in principle impossible to determine if a theory is false by reference to evidence.

Conceptual schemes

The framework of a theory (formal conceptual scheme) is just as open to revision as the "content" of the theory. The aphorism that Quine uses is: theories face the tribunal of experience as a whole. This idea is problematic for the analytic-synthetic distinction because (in Quine's view) such a distinction supposes that some facts are true of language alone, but if conceptual scheme is as open to revision as synthetic content, then there can be no plausible distinction between framework and content, hence no distinction between the analytic and the synthetic.

One upshot of confirmational holism is the underdetermination of theories: if all theories (and the propositions derived from them) of what exists are not sufficiently determined by empirical data (data, sensory-data, evidence); each theory with its interpretation of the evidence is equally justifiable. Thus, the Greek's worldview of Homeric gods is as credible as the physicists' world of electromagnetic waves. Quine later argued for Ontological Relativity, that our ordinary talk of objects suffers from the same underdetermination and thus does not properly refer to objects.

While underdetermination does not invalidate the principle of falsifiability first presented by Karl Popper, Popper himself acknowledged that continual ad hoc modification of a theory provides a means for a theory to avoid being falsified. In this respect, the principle of parsimony, or Occam's Razor, plays a role. This principle presupposes that between multiple theories explaining the same phenomenon, the simplest theory--in this case, the one that is least susceptible to continual ad hoc modification--is to be preferred.

References

- Curd, Martin; Cover, J.A. (Eds.) (1998). Philosophy of Science, Section 3, The Duhem-Quine Thesis and Underdetermination, W.W. Norton & Company.

- W. V. Quine. 'Two Dogmas of Empiricism.' The Philosophical Review, 60 (1951), pp. 20-43.

- W. V. Quine. Word and Object. Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press, 1960.

- W. V. Quine. 'Ontological Relativity.' In Ontological Relativity and Other Essays, New York, Columbia University Press, 1969, pp. 26-68.

- D. Davidson. 'On the Very Idea of Conceptual Scheme.' Proceedings of the American Philosophical Association, 17 (1973-74), pp. 5-20.