Propositional logic

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In mathematical logic, propositional logic or sentential logic is the logic of mathematical objects called propositions. These objects are typically represented in various formal systems called propositional calculi or sentential calculi. The latter are formal deduction systems whose atomic formulas are propositional variables.

In general terms, a calculus is a formal system that consists of a set of syntactic expressions (well-formed formulae, formulas, or wffs), a distinguished subset of these expressions, plus a set of transformation rules that define a binary relation on the space of expressions.

When the expressions are interpreted for mathematical purposes, the transformation rules are typically intended to preserve some type of semantic equivalence relation among the expressions. In particular, when the expressions are intepreted as a logical system, the semantic equivalence is typically intended to be logical equivalence. In this setting, the transformation rules can be used to derive logically equivalent expressions from any given expression. These derivations include as special cases (1) the problem of simplifying expressions and (2) the problem of deciding whether a given expression is equivalent to an expression in the distinguished subset, typically interpreted as the subset of logical axioms.

The set of axioms may be empty, a nonempty finite set, a countably infinite set, or given by axiom schemata. A formal grammar recursively defines the expressions and well-formed formulas (wffs) of the language. In addition a semantics is given which defines truth and valuations (or interpretations). It allows us to determine which wffs are valid, that is, are theorems.

The language of a propositional calculus consists of (1) a set of primitive symbols, variously referred to as atomic formulas, placeholders, proposition letters, or variables, and (2) a set of operator symbols, variously interpreted as logical operators or logical connectives. A well-formed formula (wff) is any atomic formula or any formula that can be built up from atomic formulas by means of operator symbols.

The following outlines a standard propositional calculus. Many different formulations exist which are all more or less equivalent but differ in (1) their language, that is, the particular collection of primitive symbols and operator symbols, (2) the set of axioms, or distingushed formulas, and (3) the set of transformation rules that are available.

Contents |

Grammar

The language consists of:

- The capital letters of the alphabet, standing as propositional variables. These are atomic formulae. Conventionally, either the Latin alphabet (A, B, C) or the Greek alphabet (χ, φ, ψ) is used, but the two are not mixed.

- Symbols denoting the following connectives (or logical operators): ¬, ∧, ∨, →, ↔. (We may do with fewer operators (and thus symbols) by having some abbreviate others — e.g. P → Q is equivalent to ¬P ∨ Q.) Many authors prefer the tilde, ~, to represent the logical not. The ampersand, &, is also a common symbol for the logical conjunction.

- The left and right parentheses: (, ).

The set of well-formed formulas (wffs) is recursively defined by the following rules:

- Basis: Letters of the alphabet (usually capitalized such as A, B, φ, χ, etc.) are wffs.

- Inductive clause I: If φ is a wff, then ¬φ is a wff.

- Inductive clause II: If φ and ψ are wffs, then (φ ∧ ψ), (φ ∨ ψ), (φ → ψ), and (φ ↔ ψ) are wffs.

- Closure clause: Nothing else is a wff.

Repeated applications of these three rules permit the generation of complex wffs. For example:

- By rule 1, A is a wff.

- By rule 2, ¬A is a wff.

- By rule 1, B is a wff.

- By rule 3, (¬A ∨ B) is a wff.

Calculus

For simplicity, we will use a natural deduction system, which has no axioms; or, equivalently, which has an empty axiom set.

Derivations using our calculus will be laid out in the form of a list of numbered lines, with a single wff and a justification on each line. Any premises will be at the top, with a "p" for their justification. The conclusion will be on the last line. A derivation will be considered complete if every line follows from previous ones by correct application of a rule. (For a contrasting approach, see proof-trees).

Axioms

Our axiom set is the empty set.

Inference rules

Our propositional calculus has ten inference rules. These rules allow us to derive other true formulae given a set of formulae that are assumed to be true. The first eight simply state that we can infer certain wffs from other wffs. The last two rules however use hypothetical reasoning in the sense that in the premise of the rule we temporarily assume an (unproven) hypothesis to be part of the set of inferred formulae to see if we can infer a certain other formula. Since the first eight rules don't do this they are usually described as non-hypothetical rules, and the last two as hypothetical rules.

- Double negative elimination

- From the wff ¬¬φ, we may infer φ

- Conjunction introduction

- From any wff φ and any wff ψ, we may infer (φ ∧ ψ).

- Conjunction elimination

- From any wff (φ ∧ ψ), we may infer φ and ψ

- Disjunction introduction

- From any wff φ, we may infer (φ ∨ ψ) and (ψ ∨ φ), where ψ is any wff.

- Disjunction elimination

- From the wffs of the form (φ ∨ ψ), (φ → χ), and (ψ → χ), we may infer χ.

- Biconditional introduction

- From the wffs of the form (φ → ψ) and (ψ → φ), we may infer (φ ↔ ψ).

- Biconditional elimination

- From the wff (φ ↔ ψ), we may infer (φ → ψ) and (ψ → φ).

- Modus ponens

- From the wffs of the form φ and (φ → ψ), we may infer ψ.

- Conditional proof

- If ψ can be derived while assuming the hypothesis φ, we may infer (φ → ψ).

- Reductio ad absurdum

- If we can derive both ψ and ¬ψ while assuming the hypothesis φ, we may infer ¬φ.

| Basic argument forms of the calculus | ||

| Name | Sequent | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Modus Ponens | ((p → q) ∧ p) ├ q | if p then q; p; therefore q |

| Modus Tollens | ((p → q) ∧ ¬q) ├ ¬p | if p then q; not q; therefore not p |

| Hypothetical Syllogism | ((p → q) ∧ (q → r)) ├ (p → r) | if p then q; if q then r; therefore, if p then r |

| Disjunctive Syllogism | ((p ∨ q) ∧ ¬p) ├ q | Either p or q; not p; therefore, q |

| Constructive Dilemma | ((p → q) ∧ (r → s) ∧ (p ∨ r)) ├ (q ∨ s) | If p then q; and if r then s; but either p or r; therefore either q or s |

| Destructive Dilemma | ((p → q) ∧ (r → s) ∧ (¬q ∨ ¬s)) ├ (¬p ∨ ¬r) | If p then q; and if r then s; but either not q or not s; therefore either not p or not r |

| Simplification | (p ∧ q) ├ p | p and q are true; therefore p is true |

| Conjunction | p, q ├ (p ∧ q) | p and q are true separately; therefore they are true conjointly |

| Addition | p ├ (p ∨ q) | p is true; therefore the disjunction (p or q) is true |

| Composition | ((p → q) ∧ (p → r)) ├ (p → (q ∧ r)) | If p then q; and if p then r; therefore if p is true then q and r are true |

| De Morgan's Theorem (1) | ¬(p ∧ q) ├ (¬p ∨ ¬q) | The negation of (p and q) is equiv. to (not p or not q) |

| De Morgan's Theorem (2) | ¬(p ∨ q) ├ (¬p ∧ ¬q) | The negation of (p or q) is equiv. to (not p and not q) |

| Commutation (1) | (p ∨ q) ├ (q ∨ p) | (p or q) is equiv. to (q or p) |

| Commutation (2) | (p ∧ q) ├ (q ∧ p) | (p and q) is equiv. to (q and p) |

| Association (1) | (p ∨ (q ∨ r)) ├ ((p ∨ q) ∨ r) | p or (q or r) is equiv. to (p or q) or r |

| Association (2) | (p ∧ (q ∧ r)) ├ ((p ∧ q) ∧ r) | p and (q and r) is equiv. to (p and q) and r |

| Distribution (1) | (p ∧ (q ∨ r)) ├ ((p ∧ q) ∨ (p ∧ r)) | p and (q or r) is equiv. to (p and q) or (p and r) |

| Distribution (2) | (p ∨ (q ∧ r)) ├ ((p ∨ q) ∧ (p ∨ r)) | p or (q and r) is equiv. to (p or q) and (p or r) |

| Double Negation | p ├ ¬¬p | p is equivalent to the negation of not p |

| Transposition | (p → q) ├ (¬q → ¬p) | If p then q is equiv. to if not q then not p |

| Material Implication | (p → q) ├ (¬p ∨ q) | If p then q is equiv. to either not p or q |

| Material Equivalence (1) | (p ↔ q) ├ ((p → q) ∧ (q → p)) | (p is equiv. to q) means, (if p is true then q is true) and (if q is true then p is true) |

| Material Equivalence (2) | (p ↔ q) ├ ((p ∧ q) ∨ (¬q ∧ ¬p)) | (p is equiv. to q) means, either (p and q are true) or ( both p and q are false) |

| Exportation | ((p ∧ q) → r) ├ (p → (q → r)) | from (if p and q are true then r is true) we can prove (if q is true then r is true, if p is true) |

| Importation | (p → (q → r)) ├ ((p ∧ q) → r) | |

| Tautology | p ├ (p ∨ p) | p is true is equiv. to p is true or p is true |

| Tertium non datur (Law of Excluded Middle) | ├ (p ∨ ¬ p) | p or not p is true |

Example of a proof

The following is an example of a (syntactical)

demonstration:

Prove: A → A

Proof:

| Number | wff | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | p |

| 2 | A ∨ A | From (1) by disjunction introduction |

| 3 | (A ∨ A) ∧ A | From (1) and (2) by conjunction introduction |

| 4 | A | From (3) by conjunction elimination |

| 5 | A ├ A | Summary of (1) through (4) |

| 6 | ├ A → A | From (5) by conditional proof |

Interpret A ├ A as "Assuming A, infer A". Read ├ A → A as "Assuming nothing, infer that A implies A," or "It is a tautology that A implies A," or "It is always true that A implies A."

Soundness and completeness of the rules

The crucial properties of this set of rules are that they are sound and complete. Informally this means that the rules are correct and that no other rules are required. These claims can be made more formal as follows.

We define a truth assignment as a function that maps propositional variables to true or false. Informally such a truth assignment can be understood as the description of a possible state of affairs (or possible world) where certain statements are true and others are not. The semantics of formulae can then be formalized by defining for which "state of affairs" they are considered to be true, which is what is done by the following definition.

We define when such a truth assignment A satisfies a certain wff with the following rules:

- A satisfies the propositional variable P iff A(P) = true

- A satisfies ¬φ iff A does not satisfy φ

- A satisfies (φ ∧ ψ) iff A satisfies both φ and ψ

- A satisfies (φ ∨ ψ) iff A satisfies at least one of either φ or ψ

- A satisfies (φ → ψ) iff it is not the case that A satisfies φ but not ψ

- A satisfies (φ ↔ ψ) iff A satisfies both φ and ψ or satisfies neither one of them

With this definition we can now formalize what it means for a formula φ to be implied by a certain set S of formulae. Informally this is true if in all worlds that are possible given the set of formulae S the formula φ also holds. This leads to the following formal definition: We say that a set S of wffs semantically entails (or implies) a certain wff φ if all truth assignments that satisfy all the formulae in S also satisfy φ.

Finally we define syntactical entailment such that φ is syntactically entailed by S iff we can derive it with the inference rules that were presented above in a finite number of steps. This allows us to formulate exactly what it means for the set of inference rules to be sound and complete:

- Soundness

- If the set of wffs S syntactically entails wff φ then S semantically entails φ

- Completeness

- If the set of wffs S semantically entails wff φ then S syntactically entails φ

For the above set of rules this is indeed the case.

Sketch of a soundness proof

(For most logical systems, this is the comparatively "simple" direction of proof)

Notational conventions: Let "G" be a variable ranging over sets of sentences. Let "A", "B", and "C" range over sentences. For "G syntactically entails A" we write "G proves A". For "G semantically entails A" we write "G implies A".

We want to show: (A)(G)(If G proves A then G implies A)

We note that "G proves A" has an inductive definition, and that gives us the immediate resources for demonstrating claims of the form "If G proves A then ..." So our proof proceeds by induction.

- I. Basis. Show: If A is a member of G then G implies A

- [II. Basis. Show: If A is an axiom, then G implies A]

- III. Inductive step:

-

- (a) Assume for arbitrary G and A that if G proves

A then G implies A. (If necessary, assume this for

arbitrary B, C, etc. as well)

- (b) For each possible application of a rule of inference to A, leading to a new sentence B, show that G implies B.

- (a) Assume for arbitrary G and A that if G proves

A then G implies A. (If necessary, assume this for

arbitrary B, C, etc. as well)

(N.B. Basis Step II can be omitted for the above calculus, which is a natural deduction system and so has no axioms. Basically, it involves showing that each of the axioms is a (semantic) logical truth.)

The Basis step(s) demonstrate(s) that the simplest provable sentences from G are also implied by G, for any G. (The is simple, since the semantic fact that a set implies any of its members, is also trivial.) The Inductive step will systematically cover all the further sentences that might be provable--by considering each case where we might reach a logical conclusion using an inference rule--and shows that if a new sentence is provable, it is also logically implied. (For example, we might have a rule telling us that from "A" we can derive "A or B". In III.(a) We assume that if A is provable it is implied. We also know that if A is provable then "A or B" is provable. We have to show that then "A or B" too is implied. We do so by appeal to the semantic definition and the assumption we just made. A is provable from G, we assume. So it is also implied by G. So any semantic valuation making all of G true makes A true. But any valuation making A true makes "A or B" true, by the defined semantics for "or". So any valuation which makes all of G true makes "A or B" true. So "A or B" is implied.) Generally, the Inductive step will consist of a lengthy but simple case-by-case analysis of all the rules of inference, showing that each "preserves" semantic implication.

By the definition of provability, there are no sentences provable other than by being a member of G, an axiom, or following by a rule; so if all of those are semantically implied, the deduction calculus is sound.

Sketch of completeness proof

(This is usually the much harder direction of proof.)

We adopt the same notational conventions as above.

We want to show: If G implies A, then G proves A. We proceed by contraposition: We show instead that If G does not prove A then G does not imply A.

- I. G does not prove A. (Assumption)

- II. If G does not prove A, then we can construct an

(infinite) "Maximal Set", G*, which is a superset of G and which

also does not prove A.

- (a)Place an "ordering" on all the sentences in the language. (e.g., alphabetical ordering), and number them E1, E2, ...

- (b)Define a series Gn of sets (G0, G1 ... ) inductively, as follows. (i)G0 = G. (ii) If {Gk, E(k+1)} proves A, then G(k+1) = Gk. (iii) If {Gk, E(k+1)} does not prove A, then G(k+1) = {Gk, E(k+1)}

- (c)Define G* as the union of all the Gn. (That is, G* is the set of all the sentences that are in any Gn).

- (d) It can be easily shown that (i) G* contains (is a superset of) G (by (b.i)); (ii) G* does not prove A (because if it proves A then some sentence was added to some Gn which caused it to prove A; but this was ruled out by definition); and (iii) G* is a "Maximal Set" (with respect to A): If any more sentences whatever were added to G*, it would prove A. (Because if it were possible to add any more sentences, they should have been added when they were encountered during the construction of the Gn, again by definition)

- III. If G* is a Maximal Set (wrt A), then it is "truth-like". This means that it contains the sentence "A" only if it does not contain the sentence not-A; If it contains "A" and contains "If A then B" then it also contains "B"; and so forth.

- IV. If G* is truth-like there is a "G*-Canonical" valuation of the language: one that makes every sentence in G* true and everything outside G* false while still obeying the laws of semantic composition in the language.

- V. A G*-canonical valuation will make our original set G all true, and make A false.

- VI. If there is a valuation on which G are true and A is false, then G does not (semantically) imply A.

Alternative calculus

It is possible to define another version of propositional calculus, which defines most of the syntax of the logical operators by means of axioms, and which uses only one inference rule.

Axioms

Let φ, χ and ψ stand for well-formed formulae. (The wff's themselves would not contain any Greek letters, but only capital Roman letters, connective operators, and parentheses.) Then the axioms are

- THEN-1: φ → (χ → φ)

- THEN-2: (φ → (χ → ψ)) → ((φ → χ) → (φ → ψ))

- AND-1: φ ∧ χ → φ

- AND-2: φ ∧ χ → χ

- AND-3: φ → (χ → (φ ∧ χ))

- OR-1: φ → φ ∨ χ

- OR-2: χ → φ ∨ χ

- OR-3: (φ → ψ) → ((χ → ψ) → (φ ∨ χ → ψ))

- NOT-1: (φ → χ) → ((φ → ¬χ) → ¬ φ)

- NOT-2: φ → (¬φ → χ)

- NOT-3: φ ∨ ¬φ

Axiom THEN-2 may be considered to be a "distributive property of implication

with respect to implication."

Axioms AND-1 and AND-2 correspond to

"conjunction elimination". The relation between AND-1 and AND-2 reflects the

commutativity of the conjunction operator.

Axiom AND-3 corresponds to

"conjunction introduction."

Axioms OR-1 and OR-2 correspond to "disjunction

introduction." The relation between OR-1 and OR-2 reflects the commutativity of

the disjunction operator.

Axiom NOT-1 corresponds to "reductio ad

absurdum."

Axiom NOT-2 says that "anything can be deduced from a

contradiction."

Axiom NOT-3 is called "tertium non

datur" (Latin:

"a third is not given") and reflects the semantic valuation of propositional

formulae: a formula can have a truth-value of either true or false. There is no

third truth-value, at least not in classical logic. Intuitionistic

logicians do not accept the axiom NOT-3.

Inference rule

The inference rule is modus ponens:

.

.

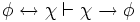

If the double-arrow equivalence operator is also used, then the following "natural" inference rules may be added:

- IFF-1:

- IFF-2:

Meta-inference rule

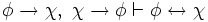

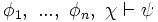

Let a demonstration be represented by a sequence, with hypotheses to the left of the turnstile and the conclusion to the right of the turnstile. Then the deduction theorem can be stated as follows:

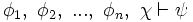

- If the sequence

- has been demonstrated, then it is also possible to demonstrate the sequence

.

.

This deduction theorem (DT) is not itself formulated with propositional calculus: it is not a theorem of propositional calculus, but a theorem about propositional calculus. In this sense, it is a meta-theorem, comparable to theorems about the soundness or completeness of propositional calculus.

On the other hand, DT is so useful for simplifying the syntactical proof process that it can be considered and used as another inference rule, accompanying modus ponens. In this sense, DT corresponds to the natural conditional proof inference rule which is part of the first version of propositional calculus introduced in this article.

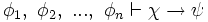

The converse of DT is also valid:

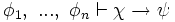

- If the sequence

- has been demonstrated, then it is also possible to demonstrate the sequence

in fact, the validity of the converse of DT is almost trivial compared to that of DT:

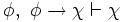

- If

- then

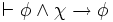

- 1:

- 2:

- 2:

- and from (1) and (2) can be deduced

- 3:

- by means of modus ponens, Q.E.D.

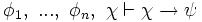

The converse of DT has powerful implications: it can be used to convert an axiom into an inference rule. For example, the axiom AND-1,

can be transformed by means of the converse of the deduction theorem into the inference rule

which is conjunction elimination, one of the ten inference rules used in the first version (in this article) of the propositional calculus.

Example of a proof

The following is an example of a (syntactical) demonstration, involving only

axioms THEN-1 and THEN-2:

Prove: A → A (Reflexivity of

implication).

Proof:

- 1. (A → ((A → A) → A)) → ((A →

(A → A)) → (A → A))

- Axiom THEN-2 with φ = A, χ = A → A, ψ = A

- 2. A → ((A → A) → A)

- Axiom THEN-1 with φ = A, χ = A → A

- 3. (A → (A → A)) → (A → A)

- From (1) and (2) by modus ponens.

- 4. A → (A → A)

- Axiom THEN-1 with φ = A, χ = A

- 5. A → A

- From (3) and (4) by modus ponens.

Other logical calculi

Propositional calculus is about the simplest kind of logical calculus in any current use. (Aristotelian "syllogistic" calculus, which is largely supplanted in modern logic, is in some ways simpler--but in other ways more complex--than propositional calculus.) It can be extended in several ways.

The most immediate way to develop a more complex logical calculus is to introduce rules that are sensitive to more fine-grained details of the sentences being used. When the "atomic sentences" of propositional logic are broken up into terms, variables, predicates, and quantifiers, they yield first-order logic, or first-order predicate logic, which keeps all the rules of propositional logic and adds some new ones. (For example, from "All dogs are mammals" we may infer "If Rover is a dog then Rover is a mammal.)

With the tools of first-order logic it is possible to formulate a number of theories, either with explicit axioms or by rules of inference, that can themselves be treated as logical calculi. Arithmetic is the best known of these; others include set theory and mereology.

Modal logic also offers a variety of inferences that cannot be captured in propositional calculus. For example, from "Necessarily p" we may infer that p. From p we may infer "It is possible that p".

Many-valued logics are those allowing sentences to have values other than true and false. (For example, neither and both are standard "extra values"; "continuum logic" allows each sentence to have any of an infinite number of "degrees of truth" between true and false.) These logics often require calculational devices quite distinct from propositional calculus.